Behaviour changes

- Introduction

- Analysing

Probelm Behaviour - Behaviour

management - Understanding

Anger - Escalating

situations - Sexual

disinhibition

Introduction

Traumatic brain injuury can cause behaviour changes.

Its helpful to start with analysing the problem behaviour and then develop strategies.

Analysing problem behaviour

Analysing problem behaviour checklist

- When does it occur?

- Where does it occur?

- Who does the behaviour occur with?

- Does it start suddenly or build up gradually?

- How long does it last?

- What is the history of the problem?

- What solutions have been tried in the past?

- How are people reacting?

Other factors to consider when analysing problem behaviour

- Physical factors ie: excess noise, overcrowding, appropriateness of house or room.

- Are they treated with respect?

- Are they part of the decision making process/do they have choices?

- Are they able to communicate effectively?

- Will they benefit from being taught coping skills ie: relaxation etc

Behaviour management techniques

There are behaviour management techniques and concepts that can be useful in managing behaviour changes following a TBI

Positive reinforcement

This serves to maintain or increase behaviour, as a result of the individual seeing the consequence of the behaviour as something positive. Positive reinforcement can be tangible (If I work hard, I will get a raise) or social (praise or smile).

Negative reinforcement

This also serves to maintain or increase behaviour. In this case we do something to prevent a negative outcome. Negative reinforcement can be tangible (If I stick to the speed limit, I will avoid a fine and I will keep my licence) or social (being ignored).

Punishment

Punishment is when something unpleasant follows a behaviour, which results in a reduction of the behaviour. For example, ‘The last time I punched someone, I ended up in jail – This time I will not use violence, I will walk away’.

Extinction

This occurs when you withhold reinforcement for a specific behaviour. It is common when using extinction to see an initial increase in the behaviour. For example, making a commitment to totally ignore inappropriate comments made by a person with TBI will initially result in the person becoming more vocal and explicit. Continue to ignore inappropriate comments and they should decrease/cease over time.

Differential reinforcement of other behaviour (DRO)

DRO involves reinforcing someone for not engaging in a particular behaviour. There are many different types of DRO, such as differential reinforcement of alternative responses or differential reinforcement of incompatible responses. With DRO any response, whether it is desirable or not, is reinforced so long as it is not the response to be eliminated. For example, if your goal is to encourage an individual to socialise with others, they would be rewarded for just coming out of their room, whether they participated in the program/ talked with others or not.

Timeout

Timeout is when a person is removed from the source of reinforcement for a specific period of time. Timeout may refer to isolation, as in a timeout room, or contingent observation, such as being able to watch activities but not participate in them. Timeout should be no longer than five minutes.

Time out on the spot (known as TOOTS) simply involves walking away from the person without saying anything to give them time to calm down. Return a few minutes later and continue your interaction with them.

Response cost

A response cost is the ‘price paid’ when an individual exhibits an undesirable response, which results in a loss of privileges or other reinforcement. For example, if you use a point/token system, you start with a set number of points/tokens and the person is 'charged' a predefined number of points/tokens for a particular undesirable behaviour. At the end of the week/time period, the points would earn them a reward. For example, ‘If you have over 80 points left you can buy the motor bike magazine you want’.

Overcorrection

There are two types of overcorrection procedures that you may be familiar with. During restitutional training, a person is required to make restitution by returning the environment to a better condition than its original state. For example, if you throw some rubbish out in the driveway – then you have to pick up all the rubbish in the driveway. The other type, positive practice, involves the person practicing the correct response repeatedly. For example – if someone does something in a sloppy fashion, then they not only do that task over again but must also perform another task neatly.

Understanding anger

Anger management problems can stem from the brain injury itself, as well as from problems with reduced self-control, impulsivity and lowered frustration tolerance. It is important to be able to:

- a) identify potential triggers of anger

- b) identify 'early warning signals’

- c) understand an emotional model of anger

- d) recognise your feelings and

- e) have strategies for managing clients who display anger.

Potential triggers of anger following a TBI

Potential triggers of anger following a TBI include the following:

- Lack of Sleep

- Pain/headaches

- Noise sensitivity

- Changed self image

- Feeling angry about accident or injury

- Worries about future/finances

- Coping with change

- Lack of understanding from others (friends/family/medical professionals etc)

- Frustration (personal and/or sexual)

- Feeling out of control when organising daily life due to numerous medical/legal appointments

- Personality clashes/changes to relationships and social activities

Early warning signals

As a person becomes angry, changes occur at a physical, emotional and/or cognitive level. If these changes are caught early enough (i.e. before a person loses their temper) then they can be used as an ‘early warning system’.

The following changes are often used as guideposts to alert a person that they are becoming angry.

Physical |

Emotional |

Cognitive |

Muscle tension Temperature change Tremor/shaking Sweating Heart pounding Clenched fists |

Irritated Frustrated Moody Unsettled Feeling upset |

Changes to thoughts include: Racing Jumbled Irrational Jumping to conclusions |

Principles of anger

To better understand how to manage anger it is useful to understand the principles of anger that include:

- a scale of anger - for example calm (no anger) to aggressive.

- an anger model showing triggers and responses

- recognition that anger can be a secondary feeling

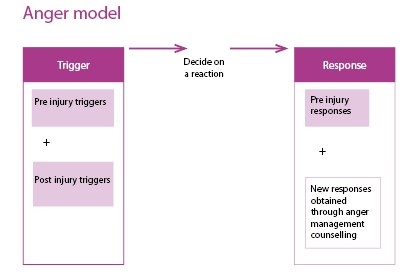

Graphics : Triggers and responses - Anger as a secondary feeling

Scale of anger

Anger escalates in intensity if it is not monitored or managed. A calm person can become angry and then aggressive, if triggered.

Triggers and responses

In thinking about how people with TBI can change from being calm to being angry or aggressive it is useful to think about triggers and responses (both pre-injury and post-injury).

Anger as a secondary feeling

Anger can be a secondary feeling and so it is important to ask the question: was there a primary feeling?

Recognising your Feelings

Remember that the behaviour is not necessarily directed at you.

Why is the person angry with you?

Proximity

What are you feeling?

It is important to recognise and identify your feelings.

What to do in relation to your feelings?

- Accept your own feelings about the situation

- Talk to family, staff & friends and discuss how you are feeling

- Recognise that you are only human and that you can also be affected by stress, frustration and anger

- Use stress and anger management strategies yourself

Strategies for staff managing clients who display anger

In any difficult situation it is important to maintain focus on the problem not the behaviour.

You can achieve this by:

- Remaining calm

- Walking away/removing yourself from situation temporarily (if safe/appropriate to do so) to regain composure

- Use non-threatening/relaxed body language and tone

- Take slow deep breaths/use a deep breathing technique

- Discontinue a conversation/discussion that is eliciting a negative emotional reaction in you or the client

- Avoid compounding the problem with the use of alcohol or drugs to ‘cope’

- Requesting a break from the client (either permanently or temporarily)

Managing escalating situations

The key steps in managing an escalating situation are:

a) Maintain self control

- Avoid mirroring behaviour

- Control breathing

- Control voice

- Control stance

- Match verbal to non-verbal behaviours

b) Maintain a safe distance

- Danger zone is 0 .4 metre to 1 metre from the person (within hitting and kicking distance)

- The area either side of the danger zone is considered safe

c) Maintain a non confrontational body stance

- Keep hands open and in full view

- Stand slightly at an angle to the person

- Avoid staring or standing with your hands on your hips

- Avoid making fast movements

d) Analyse situation

- Is there anything reinforcing the behaviour?

- Is there anything frightening the person?

- Are they being over or under stimulated?

e) Decide on an intervention

- Intervention can include negotiation, leaving, no action, surprise, diversion, humour, isolating client, removal of other clients/people, requesting assistance and evasive self defence (only to be used if under attack / as a last resort)

f) Review intervention and decide on next step

- Monitor situation and intervention. This will help you decide whether or not to continue, modify or stop the current intervention.

g) Managing after a crisis

The body’s normal internal reaction to stress is a build up of tension.

Tension can be released by:

- Relaxation / breathing techniques

- Vigorous activity or aerobic exercise (physical release)

- Talking, laughter, crying (emotional release)

Things to avoid

- Self-administering drugs/overuse of prescribed medication

- Using alcohol, caffeine or cigarettes

- Using food as a means to cope

- Releasing tension by aggression and anger

Things to remember

- after any crisis, it is normal for a person to experience an emotional or physical change for up to six weeks

- don’t label yourself as crazy

- avoid making life-altering decisions within a few weeks of the crisis

- seek professional help if symptoms persist longer than six weeks.

Understanding and Managing Sexual Disinhibition

Injury to the frontal lobes is common after a TBI and it is the frontal lobes that help us to control our behaviour and behave appropriately in different situations.

Therefore, after suffering a brain injury some people exhibit inappropriate behaviours.

Although this behaviour is a result of the brain injury it is possible to help them control the behaviour by changing the way we interact with them.

When people behave in a sexually inappropriate way it is important that everyone responds in the same way to the behaviour, to reduce the frequency and, hopefully, eliminate it. Sometimes staff and family members will feel embarrassed by such behaviour and will laugh to cover up their embarrassment. While this is understandable, this sort of response is likely to encourage the patient to continue so it’s important to adopt a firm, ‘matter of fact’ tone of voice when talking to him. At the same time it’s important not to display anger or disgust in your manner or voice as the patient may derive some satisfaction from this so be as neutral as possible.

Strategies

- When a person makes a sexually inappropriate remark, say to him, using a firm, calm tone of voice, “I don’t like you saying those things so stop now”. You don’t have to use these exact words; say whatever you feel comfortable with.

- Change the topic of conversation immediately

- If the person can’t be distracted to another topic of conversation or if you feel too uncomfortable to stay, walk away from the person immediately without saying anything further.

- If it’s not possible to leave because you’re in the middle of carrying out some procedure (eg. helping him to shower) then continue on with what you were doing and don’t enter into any further discussion about his remarks. If he continues to make inappropriate remarks, ignore him and don’t make any eye contact. Then leave as soon as you’ve finished.

- However, if he continues to make remarks and it is possible to leave him safely, then leave the room without further discussion. Go back after a few minutes, don’t make any reference to the previous remarks and continue again with what you were doing. If the behaviour starts again, tell him you don’t like it and walk away again.

- If the person is touching himself in an inappropriate way say “You’re not to do that when other people are with you”

- If the person touches you in an inappropriate manner tell him to stop immediately.

- If the person later apologises for his remarks/behaviour don’t get into a discussion about the matter. Say something along the lines of “OK let’s forget about it now” then continue on with what you were doing and change the topic of conversation. Sometimes people will apologise but then get some satisfaction from continuing to go on apologising excessively.

If you know that someone has the potential to be sexually inappropriate it is important to be careful about topics of conversation if you’re chatting to him. People will often ask personal (and seemingly innocent) questions about whether you have a boyfriend/are married etc. They then go on to ask for increasingly personal information such as are you happy with your boyfriend etc. which then leads onto sexually inappropriate remarks/behaviour. When someone first asks a personal question it is better to say “Look I’m your (eg nurse) and sorry but I don’t talk about personal information” (or use whatever words you feel comfortable with). Then start to talk about something else.