Injury . . . Effects . . . Impairments . . . Impacts

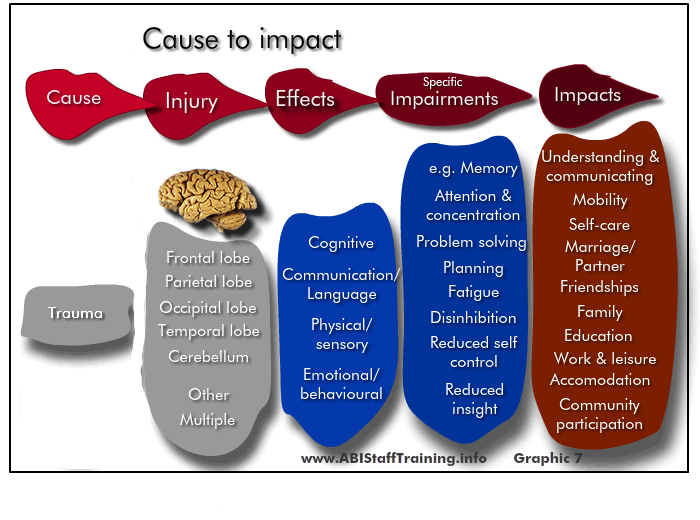

Cause to impact

The TBI makes a physical injury to the brain (in one or more parts of the brain) which in turn has an effect in areas such as cognition, communication and language, etc which can be seen through specific impairments (e.g. memory difficulty, difficulty with problem solving) and these in turn impact on the person's life ( self-care, relationships, work).

Each person with an TBI is different because:

- the exact nature of the injury to the brain is different from one person with an TBI to the next and

- this in turn means the general effects and specific impairments are different from one person with TBI to the next and

- this in turn means the impacts on life of the person with TBI are different from one person with TBI to the next.

Introduction

Common effects of Traumatic Brain Injury include:

- Cognitive

- Communication/language

- Physical/sensory

- Emotional/behavioural/personality

There is overlap and interconnections between these effects. The specific effects will be unique to each individual and their injury. The extent of the effects and challenges for the person with brain injury depends on:

- The severity of the TBI

- The location of the brain damage in TBI

- The length of time since brain injury

- The extent a person has been able to integrate back into the community

- The support available to the person.

Impairments following TBI

Each traumatic brain injury is unique and severity varies greatly from one person to the next. The specific impairments and the impact on functioning are particular to each person. These can be profound and long-term with personality and behaviour change leading to significant lifestyle effects that flow from neurological and cognitive impairment, as summarised in the Table below.

Category |

Specific Impairment |

Neurological impairment (motor, sensory and autonomic) |

|

Cognitive impairment |

|

Personality and behavioural changes |

|

Psychological distress and adjustment challenges after TBI

Psychological distress post TBI is highly prevalent after a TBI and can present with mixed mental health issues with features of depression, anxiety, anger and stress.

Gould, K. R., Ponsford, J. L., Johnston, L., & Schönberger, M. (2011). The nature, frequency and course of psychiatric disorders in the first year after traumatic brain injury: A prospective study. Psychological Medicine, 41(10), 2099-2109.

Changes in behaviour

Sabaz et al found that challenging behaviours for community-dwelling adults with severe TBI were widespread, having an overall prevalence rate of 54% - with inappropriate social behaviour, verbal aggression and adynamia being the most common.

Over one-third of the adult study sample displayed more than one type of challenging behaviour

Behaviour can include impulsivity, self-centeredness, increased anger or aggression, apathy, disinhibition, and problems with initiation and task completion (Ponsford et al 2013; Sabaz et al 2014).

51% of 8-18 year olds who were active clients of the paediatric BIRPs and living in the community met criteria for challenging behaviour. While the most prevalent challenging behaviours were the same as for adults (inappropriate social behaviour, verbal aggression and adynamia) the prevalence across all the remaining categories was different.

Co-morbidities

In the Sabaz et al study, co-morbidities were explored using the HoNOS-ABI. Adults with pre-existing mental health or drug and alcohol issues were more likely to exhibit challenging behaviour following a TBI. 122/276 rated as having challenging behaviours plus at least one of the comorbid mental health conditions at a moderate/severe level. Challenging behaviours were significantly associated with the presence of comorbid drug and alcohol problems, hallucinations, depression, and other mental health issues with a trend for self-directed harm. In addition, because of their brain injury, people had difficulties accessing non-acute services to manage comorbidities once discharged home.

Physical disability

The greatest majority make a good physical recovery with few requiring mobility aids

Neurological impairments such as loss of taste, vision impairments, headaches and problems with balance can continue up to 10 years post injury. (Ponsford, Downing et al., 2014.)

Cognitive impairments

A not uncommon pattern of impairments is a mix of retained cognitive skills with areas of lower functioning. Commonly included are slowed information processing, memory and more complex thinking (dealing with complex ideas), being rigid or perseverative, lack of social awareness (Ponsford et al 2013); Tate et al 1991).

Planning and organising

People may have a number of difficulties in this area. For example, cooking a meal becomes a disaster because the steps were not done in the correct order. A lack of self-monitoring means that it can be hard for people to learn from their mistakes. Up to 48% of people with TBI reported some planning problems (Ponsford et al., 1995).

Insight

People may be unaware of their limitations or have unrealistic goals or expectations. [Typology – on the mark, over/under report of symptoms due organic reasons/denial and protectiveness (ref. Tamara Onsworth)]

Impacts and social consequences of TBI

The impairments caused by the TBI have significant impacts on the person, their life, family and friends, and ability to live and work in the community. Other areas of social impact were documented in Simpson & Yuen 2016 as being an increased risk of substance abuse, mental health problems, homelessness, social isolation and suicide.

Common lifestyle consequences

Common lifestyle consequences include:

- Unemployment and financial hardship

- Inadequate academic achievement

- Lack of transportation alternatives

- Inadequate recreational opportunities

- Difficulties in maintaining interpersonal relationships, marital breakdown

- Loss of pre-injury roles; loss of independence

- Service utilisation

Service utilisation

In the Hodgkinson et al. (2000) cohort of 119 people 6 months to 17 years post trauma, 90% had used services in the previous 12 month interval. In rank order, the largest proportion of the sample, 81%, had used medical and allied health services in the previous year, 66% had used transport, 58% services pertaining to finances, 49% legal, 40% vocational/educational, 23% accommodation, 21% day activity programs, 19% home support, and 8% had used each of crisis, respite and ethnic services.

Vocational outcomes

Vocational status as a measure of injury outcomes were highlighted in a NSW study. Those employed prior to injury were working full-time in 78% of cases. However, post-injury, only 41% of those employed were working full-time. 29% (207/721) of the sample were in open employment. There was a marked shift from full-time to part-time employment. Over half the clients (54%, 386/721) were not engaged in any work-related activity (link to VPP report ACI website).

Longer term consequences

In a very severely injured NSW cohort of 100 consecutive admissions to a regionally-based inpatient rehabilitation unit (Tate, Lulham, Broe, Strettles & Pfaff, 1989),

- 47% were unable to live independently at follow up, on average, at 6 years post-trauma.

- Marital breakdown rates during that period were 55%; of those who were not in a relationship at the time of the injury, 71% remained single, 48% had not formed any intimate relationship in the 6 years since the injury and 41% were socially isolated.

- 71% were not in any sort of employment, and indeed 39% were neither employed, nor did they engage in any other a vocational program of activity in lieu of work.