Initial treatment and diagnosis

- Initial

treatment

and diagnosis - Management of

Mild

Head Injury - What

people say

- Eighteen

Experiences

- Clinical voices:

Mis-diagnosis

- Clinical voices:

Unpredictability

of prognosis

Initial treatment and diagnosis

Recognising mild TBI can be difficult

Recognising mild TBI is critical to correct management and prevention of further injury.

However, the symptoms and signs are variable, non-specific and may be subtle.

The diagnosis of mild TBI should be made by a medical practitioner.

The diagnosis should include taking a clinical history and examination that includes a range of domains including mechanism of injury, symptoms and signs, cognitive functioning and neurological assessment including balance testing.

The difficulties with diagnosis and the uncertainty about how long recovery will take create numerous difficulties for people dealing with mild TBI, especially for those for whom symptoms don't subside within a few days or weeks.

Things to know

Mild TBI is difficult to diagnose.

One can have a mild TBI and it NOT show up on a brain CT scan.

Initial Treatment and Diagnosis: Good Practice

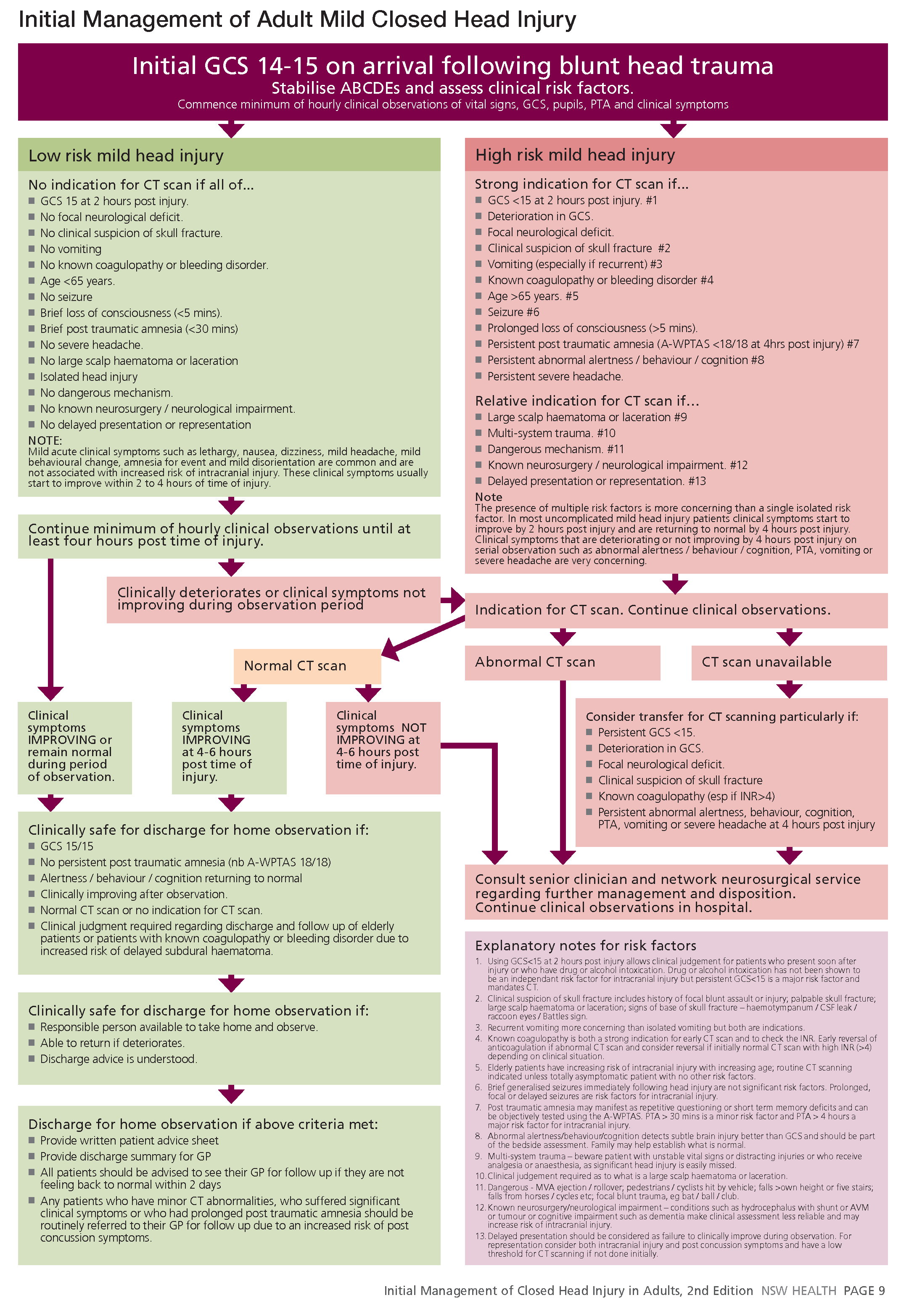

In a hospital emergency department Mild TBI is classified as Low Risk or High Risk.

Low Risk

Low risk includes for example:

- Loss of consciousness for less than five minutes

Brief post traumatic amnesia (less than 30 minutes) - No vomiting

- No severe headache

Low risk will include monitoring and if symptoms don't deteriorate you will be discharged for home observation.

High Risk

High risk includes for example:

- Loss of consciousness for more than five minutes

Brief post traumatic amnesia for more than 30 minutes - Vomiting

- Severe headache

High risk will include CT scan, monitoring and then discharge or not.

On discharge from hospital

On discharge from hospital for home observation you should receive:

■ Written patient advice sheet

■ Discharge summary for GP

■ Advice see their GP for follow up if they are not feeling back to normal within 2 days

■ Advice to see your GP if you have minor CT abnormalities, have suffered significant clinical symptoms or have had prolonged post traumatic amnesia - due to an increased risk of post concussion symptoms.

See: TAB: Initial Management of Closed Head Injury in Adults for details

What people say

Peoples reflections on their initial treatment and diagnosis.

‘Oh no, she’s all right. Send her home’.”

On the Friday night, my friends were concerned and they took me to emergency.

They thought that my pupils were different sizes from each other, and they took me down

to emergency but [the staff] rang someone and they said, ‘Oh no, she’s all right. Send her home’.”

We

literally just had to work it out for ourselves that I had a brain injury because everything was different

“In hindsight, I wish I’d been in [hospital] longer. No-one even spoke to [us] about things like post-epilepsy and things like that. We literally just had to work it out for ourselves that I had a brain injury because everything was different.”

“The [hospital] gave me a sheet of information on concussion.

“The [hospital] gave me a sheet of information on concussion. “Read this and don't drive until you recover and it would probably be a good idea to go see your doctor [in a few days] just to make sure that you're okay.” It’s taken me more than six months to recover.”

“I was told I was fine to go and would be fine.

“I was told I was fine to go and would be fine. Although I knew it wasn’t fine. I couldn’t remember anything.”

“I had a horrible experience with an emergency room doctor who said, “He’s fine. He’s just a baby who has had a sleep or has got a virus or something

“I had a horrible experience with an emergency room doctor who said, “He’s fine. He’s just a baby who has had a sleep or has got a virus or something. And I need to tell you that this is an emergency room for emergency cases.”

“There was no follow up [from the acute hospital]. I actually don’t even think they told me to go to the GP, I just decided it was a good idea to go to the GP.”

“They just basically go, ‘No, no brain bleed, concussion. Time will heal,’ and then you’re out of their system and people are completely lost.”

Eighteen Experiences: Initial treatment and diagnosis

All participants sought medical assistance in the days or weeks following injury.

Some (12/18) attended an emergency department at a local hospital, others (6/18) initially presented to their general practitioner.

A small number of participants (2/18) were satisfied that their treating clinician had identified and diagnosed their injury and provided them with the appropriate treatment, referrals and guidance about management of their injury.

For those participants who attended hospital, the most common experience was that, while substantial attention was paid to their physical injuries, there was inadequate assessment of their brain injury. This was particularly the case when there were few signs of injury evident on their brain scan.

The majority of participants who had attended hospital (10/12) felt that they had been discharged too quickly. Some (6/12) reported that they were experiencing confusion and disorientation when they left the hospital. Many described that they had received little advice about what, if any, follow up they needed (10/12). Just over half (7/12) reported that they were unaware that they had sustained a brain injury upon leaving hospital. Many participants (8/12) described that they felt they were on their own after leaving hospital and had to try and “work it out” themselves. Given their significant fatigue and cognitive changes, this was often a challenging and frustrating task.

Three participants reported that their practitioners were quick to identify and respond to their injuries and refer them to other practitioners and/or for further testing.

The lived experiences of participants highlighted that, where participants were able to be connected to specialist services early, they were able to access treatment and support that assisted a positive recovery.

Prevalence of Mis-diagnosis and Misinformation.

One prominent theme to emerge from this study was the prevalence of mis-diagnosis and misinformation that occurs with mild TBI.

Clinicians reported that their patients often had earlier experience with mis-diagnosis prior to their rehabilitation. Largely, this was a result of the fact that negative results on medical imaging such as CT scans and MRIs are typically interpreted as sufficient reason to rule out a TBI of any kind despite the fact that diagnostic technology is not yet sensitive enough to pick up these mild injuries [5].

With mild traumatic brain injury, we really do not have a medical test that’s accurate enough or detailed enough to really tell you which axons and dendrites might be sheared or which cell nuclei might be affected by the impact.

My patients say, “But, my MRI looks normal. They keep telling me my MRI is normal.”

They hear, “Based on testing, you do not have a bleed. The CT scan and the MRI is negative and so you should be able to return to work or school but just take it easy.”

The lack of clear diagnostic tests that corroborate patients’ symptomology contributes to feelings of frustration and misunderstanding. Rehabilitation professionals reported consistently hearing mTBI patients ask “Why am I having so much trouble if all my tests are normal?” In the face of symptoms that interfere with daily functioning, negative test results create a remarkably incongruous scenario, not only for patients but also for rehabilitation professionals.

Clinicians reported that their patients were also misinformed sometimes even by primary care physicians who made reassurances that mild brain injury is an uncomplicated event that resolves easily and quickly.

Family practitioners typically will tell them, “Oh, it’s four to six weeks. You’ll be better. It’ll be fine. It’s all good. Just go home, rest, do not pushyourself.”

They go to a doctor, and they do not get as much support. “You’ll be fine. You look great. Your CAT scans are normal. You know, give it a month. It’ll be fine.”

Although important, sleep and rest do not necessarily produce the expected results in the type of atypical fatigue common in mTBI [15]. When efforts to “rest and take it easy” fail to produce expected recovery, even those who pursued further medical help were at times rebuffed.

He was sent to a psychologist who was basically saying, “You need to just push yourself through the situation. You cannot give in to the anxiety. If you push yourself through and get to the other side, you’ll see that you can survive it.”

So many of our patients have been transferred from one physician to another and they haven’t really gotten a solid answer.

Clinicians were acutely aware that mTBI patients who had been referred for rehabilitation services generally need more than just rest or a motivational shove. Too often, they found that their patients were left to manage without proactive medical care to provide accurate information about the complexity or anticipated duration of symptoms related to mTBI.

Unpredictability of Prognosis.

Clinicians reported being routinely asked to give their patients a prognosis.

Once patients find mTBI professionals who understand their injuries and are sympathetic to their often-complicated experiences of seeking support, they are eager to get a reliable and predictable prognosis. In part, patient demand for a clear prognosis stems from the sociocultural expectation that doctors not only diagnose but also predict outcomes. Increasingly, medical professionals are under pressure to cure ailments in a society that resists acceptance of death, pain, and suffering [16]. Participants expressed frustration with the inability to satisfy their patients’ understandable desire for a clear and simple prognosis.

The hardest thing—a lot of people want an end date. They want an answer. They want—“When am I going to be back? When am I going to be healed? When am I going to be better?”

“You’ll be better in three months.” You know, you cannot give that promise.

I think the most challenging thing is that nobody really has a crystal ball, your ability to heal is individual and it’s based on so many factors.

Although patients want to know when they will feel better or when their situation will significantly improve, the ability to predict the duration and even severity of symptomology with a diagnosis of mTBI can be difficult [9].

You can have someone with a concussion rebound very quickly and get back to school or work without too much difficulty or you can have lingering symptoms that are very debilitating but they still have the same diagnosis.

Understandably, many mTBI patients expect the prognosis to be consistent with their conceptualization of a mild diagnosis. As rehabilitation professionals know well, however, a diagnosis of mTBI does not always provide a clear treatment strategy in which quick and significant improvement is definite. Rehabilitation professionals reported needing to manage patients’ disappointments given their expectations of recovery from a “mild” injury.

We have to help people manage expectations. We want to be encouraging at the same time not be over-encouraging, so you do not want them to look through rose-colored glasses but you do not want to dash their hopes, either.

Across the board, patients do not realize that the side effects can be something that will be long lasting, and even permanent.

The diagnostic use of the term mild can bear little relationship to the duration of symptoms or the time it takes for patients to actually feel symptom-free. The challenge for rehabilitation professionals is to keep patients motivated in the face of a complex and unpredictable injury.