Australian Defence Force

mild TBI in the Australian Defence Force

mTBIs

- 28.3% of ADF personnel have experienced at least one mTBI in their lifetime.

- 12.6% of the ADF reported being exposed to a blast or explosion IED, and 14.0%reported being exposed to an RPG.

Causes

- Motor vehicle accidents were the most prevalent cause of mTBI.

Motor vehicle accidents and falls carry a greater risk of mTBI than blast exposure.

Who

ADF members with a lifetime mTBI were more likely to be:

- male

- in the army

- older in age

- junior in rank (other ranks and non‐commissioned officers); and

- less likely to have been on operational deployment.

Impacts

- mTBI is associated with a significantly increased risk of all domains of psychological disorder.

- Post‐concussion symptoms are highly nonspecific and have a substantial overlap with psychological symptoms including PTSD.

Policy issues

- From a public health perspective, the prevention of motor accident trauma in the ADF needs to be addressed in any policy about mTBI.

- The prevalence of falls as a cause of mTBI suggests the risks associated with training and should not be underestimated from an occupational health and safety perspective.

- Given the evidence of increasing risk of permanent sequelae associated with repeated mTBI, solely focusing on the deployment exposures will miss the fact that many ADF members are likely to have had mTBI prior to deployment from non‐combat related causes.

Ways victims of domestive violence may sustain a brain injury

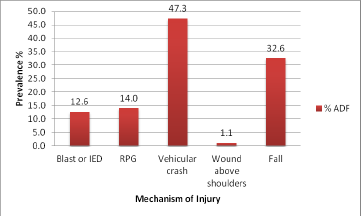

Figure 1: Lifetime prevalence of injury events in the ADF

As can be seen in Figure 1, the most common mechanism of injury in the ADF were vehicular crashes (47.3% N=23685). Over their lifetime, 32.6% (N=16321) of the ADF reported having a fall, 14%

(N=7009) were exposed to an RPG, 12.6% (N=6321) experienced a blast or explosion IED and 1.1% of (N=534) reporting having experienced a fragment wound or bullet above the shoulders.

Deployed or not deployed

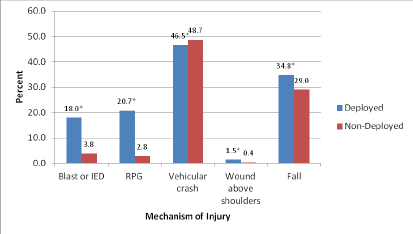

Note* = significantly different from non‐deployed group, injury events are not mutually exclusive

Figure 2. Percentages of ADF members who have experienced injury events by deployment status.

If we look at these events according to whether the ADF member had ever been on operational deployment or not (Figure 2), deployed personnel were significantly more likely to experience all types of injury events than personnel who had never deployed with the exception of vehicular accidents, where deployed personnel were less likely to be exposed (46.5% deployed vs 48.7% non‐deployed, OR=0.92 (95% CI 0.87‐0.96), p=0.0051).

For example, deployed personnel were over 5 times more likely to be exposed to a blast/IED (18% deployed vs 3.8% non‐deployed, OR = 5.6 (95% CI 5.1‐6.1), p <.0001); almost 9 times more likely to be exposed to an RPG/land mine/grenade etc (20.7% deployed vs 2.8% non‐deployed, OR = 8.9 (95% CI 8.0‐9.9), p <0001); 3.4 times more likely receive a fragment or bullet wound above the shoulders (1.5% deployed vs 0.4% non‐deployed, OR=3.4 (95% CI 2.5‐4.7), p<.0001) and 1.3 times more likely to experience a fall (34.8% deployed vs 29% non‐deployed, OR=1.3 (95% CI 1.2‐1.4), p<.0001), than non‐deployed personnel. Details of whether any of the events happened during a deployment however were not specified.

Risk of Repeat injury

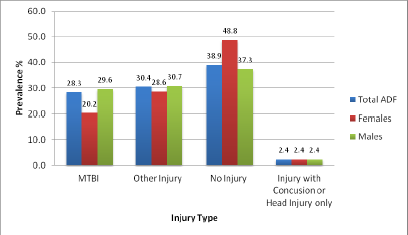

Figure 3: Lifetime prevalence of mTBI in the ADF by Sex

Based on the available data, one in three (N=14,170, 28.3%) members of the ADF met criteria for an mTBI in their lifetime. This is comprised of 16.38% who reported loss of consciousness and 11.93% reporting either being dazed or confused, or not remembering the event with no associated loss of consciousness.

A further 30.4% reported experiencing an injury event with no accompanying symptoms of mTBI

(other injury). This was the reference group for all analyses.

Finally 38.9% of the ADF reported never having experienced an injury listed in Question 1 of the mTBI screening questions.

Males were significantly more likely than females to report an mTBI compared to other injuries

(p<.0001). A small number of ADF members (2.4%) reported experiencing one of the 5 injury events with an associated concussion or head injury but no other symptoms of mTBI.

The 2010 ADF mTBI Study

Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI) in the Australian Defence Force: Results from the 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Dataset

Authors: Miranda Van Hooff PhD, BA Hons (Psych), Liz Saccone B Psych (Hons), Levina Clark B Psych (Hons), PhD (Clin Psych), Thao Tran PhD, B Sc Maths (Hons), Alexander McFarlane AO, MB BS (Hons), MD, FRANZCP, Dip Psychother

The Health and Wellbeing Survey Phase 2 –

Purpose

The purpose of this report is to examine the lifetime prevalence of self‐reported head injury in a representative sample of the ADF. Mechanisms of injury, frequency of reported post‐injury symptoms, differences between deployed and non‐deployed groups, and relationships between injury and various psychiatric disorders will also be explored. Injury groups and some analyses have been modelled on a paper by Hoge and colleagues (2008).

Method

Data used in this report was collected in 2010 as part of the 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Study (MHPWS; McFarlane, Hodson, Van Hooff, & Davies, 2011). This study aimed to measure the prevalence of 12‐month mental health disorder and psychological distress in a representative sample of currently serving ADF personnel. Trainees and reservists were not included in this study. Of the 50,049 currently serving ADF members invited to complete the survey, 24,481 responded between the 23rd of April 2010 and the 31st of January 2011.

Summary

This report is the first to determine the lifetime prevalence of mTBI in a currently serving representative military sample. Although limited in capacity for investigation of the relationship between mTBI and psychological dysfunction it provides important baseline prevalence data to inform future analyses.

An important finding was that head injury in the ADF is most commonly caused by motor vehicle accidents. The surprising finding was that the rates of mTBI were higher in non‐deployed individuals and can be accounted for by this risk of motor vehicle accidents in the Australian environment. Individuals who have been deployed have significantly higher rates of experiencing IED blasts and RPGs, as well as exposure to falls. Hence, the issue of mTBI is one that requires broad investigation and focus in the ADF environment because it is a significant risk in both deployed and non‐deployed personnel.

Post‐concussive symptoms are associated with mTBI. Careful analysis, however, demonstrates that post‐traumatic, depressive, and anxiety disorders strongly contribute to these symptoms. Hence, clinicians should not simply attribute post‐concussive symptomatology to the experience of an mTBI in the absence of a thorough psychiatric history and assessment. Hence, any assessment process in the ADF context needs to assess both mTBI post‐concussive symptomatology and psychiatric symptomatology concurrently. Solely focusing on the relationship between post‐concussive symptomatology, cognitive dysfunction, and mTBI is likely to lead to significant misattribution. In essence, this is a complex area that requires careful consideration and the development of consensus based guidelines with contributions from a broad range of domain specific experts.